Human evolution taught us to work with each other.

Neoliberalism teaches us to compete with each other.

In Part I of this series, in which I listed the 10 Tenets of Neoliberalism, I stated the following as the third tenet:

3. Because the Market is an impartial and efficient distributor of resources, wealth and income inequality is actually a moral imperative and the people who accrue more resources deserve their wealth, while the “losers” who have not been able to thrive in the Market environment must simply accept their fate because there is no sustainable alternative to the Market-based system.

The concepts of individualism, identity and self-reliance are something that form the heart of the neoliberal ethos. In the neoliberal society, we are all on our own. We cannot rely on others, indeed relying on others is considered immoral. In a neoliberal society, instead of banding together and working with each other, we are all in competition with each other.

In a world of scarcity and austerity, we are all under pressure to maximize our own value in the neoliberal System. We need to “work hard and play by the rules.” If we are poor, it is up to us — and only us — to improve our own condition through hard work, or education, or acquiring the “right” skills that are valued by the Marketplace. And of course we ourselves are responsible for acquiring or purchasing these things in an open and free Market.

Unions are Anathema to Neoliberalism

Prior to the 1980’s, trade unions in America were the institutions that helped people lift themselves out of poverty. Joining a union meant you could acquire skills, education and standing. A union member regardless of occupation could gain a position not just in an industry, but in society as a whole. The unions were the engine that drove the American Dream and fueled the upward economic mobility that was once a hallmark of life in the US.

Prior to the 1980’s, trade unions in America were the institutions that helped people lift themselves out of poverty. Joining a union meant you could acquire skills, education and standing. A union member regardless of occupation could gain a position not just in an industry, but in society as a whole. The unions were the engine that drove the American Dream and fueled the upward economic mobility that was once a hallmark of life in the US.

Unions were strong and effective, and played a big role in the American body politic because they were organised groups of many people who worked together to achieve common ends. It was the unionist movement that enabled the Democratic Party to maintain a lock on Congress for almost 70 years. Union members attended rallies and provided the foot soldiers to canvass their neighbors and get out the vote on election day.

Police and firemen, some with their wives and children, assemble on Philadelphias Rayburn Plaza, Nov. 13, 1956 to carry their wages and hours demand to City Council. The police and firemen are demanding an increase of $1,000 a year and a 40-hour week. (AP Photo/Sam Myers)

The decline of unions mirrored the rise of neoliberalism. Indeed, defanging and disempowering the unions was a major prerequisite to establishing a neoliberal order. Reagan and Thatcher, the patron saints of neoliberalism, both became famous early in their terms for “taking on” the unions and beating them. They knew instinctively that in order to institute the neoliberal order, unions would have to go.

Higher (priced) Education

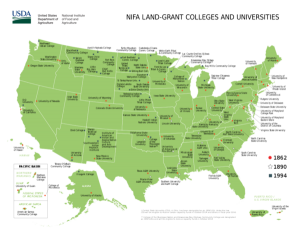

Ever wonder how it came to be that every State in the Union has a public university system? Not just New York, Massachusetts and California, but Alaska, West Virginia, Oklahoma and Mississippi?

These public universities were all established through a giant, massive and sweeping centralised program from the Federal Government. The Morrill Acts (there were multiple) actually granted the States federally owned public land to use in order to establish and operate a public university system. That is why many of these schools are called “Land Grant Universities”.

One major condition of the Land Grants was that education at these colleges and universities was to be FREE to in-State residents.

One major condition of the Land Grants was that education at these colleges and universities was to be FREE to in-State residents.

Older Americans can still remember when State universities were tuition-free. It wasn’t until the 70’s and 80’s, when a cabal of conservative Governors, led by Ronald Reagan, introduced the idea of charging tuition for public universities. Charging tuition fulfilled two explicit goals: 1) the revenue could be used to offset tax cuts, and 2) by putting a price tag on what had been free education, it forced students to be more careful on campus, avoiding confrontation with the authorities and becoming more docile. Reagan had waged war against “those hippies” at U.C. Berkeley who protested the Vietnam War all through his Governorship.

Indeed, whenever you read stories or see films about the massive student unrest and protest of the Vietnam War, it is important to keep in mind that those students were all attending college tuition-free. They (and their parents) had nothing to risk financially in demonstrating or facing expulsion.

1968: Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) staged massive campus protests across the country. Public colleges started charging tuition shortly thereafter.

But putting a price on public higher education had an even more insidious purpose: it separated America’s young people by class and by money. As I mentioned above in the 3rd Tenet of Neoliberalism, there are “winners” and “losers”. Now the country’s universities had become the province of winners determined not by academic ability, but by the ability to pay.

In 1970, Roger Freeman, a Hoover Institution economist and a key educational adviser to Nixon then working for the reelection of California Governor Ronald Reagan–defined quite precisely the target of the conservative attack on tuition free college education in an article that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle:

“We are in danger of producing an educated proletariat. That’s dynamite! We have to be selective on who we allow to go through higher education.”

Neoliberalism is a system in which everything is commoditized, including people. College education is part of a pedigree system that renders that person more valuable in the Marketplace. Of course, once college became all about scrounging to meet tuition costs through parents’ savings, loans or grants, then it was only natural to demand a Return on Investment for that money. there was no room for messing about; fewer students were willing to risk all that money by demonstrating or protesting and risking being suspended or expelled.

Reagan had achieved his goal of taming “those hippies at Berkeley,” but the effect on American society was dramatic.

Whenever you read stories or see films about the massive student unrest and protest of the Vietnam War, it is important to keep in mind that those students were all attending college tuition-free.

The “Me Generation” and Rampant Consumerism

It was during the rise of neoliberalism that segmented marketing techniques came into being. People were broken up into micro-segments and told that they were special, they were unique, and they deserved only the best.

During the 1970’s. American cars were getting steadily smaller, their fuel efficiency steadily higher. Americans were being told to save on energy, to respect the environment, to “save the ozone layer.” Environmentally-friendly detergents and other household goods were all the rage. President Carter exhorted consumers to use less energy, set their thermostats lower and wear sweaters.

That all changed in the Reagan 80’s. Environmental concerns were abandoned; bigger and better was the motto of the day. The Sports Utility Vehicle came on the scene, and fuel efficiency became a thing of the past. Americans were told they deserved the best; they had earned the best, and they should enjoy only the best.

McDonald’s Restaurants ran ads telling people “you deserve a break today.” This famous jingle led to ads targeted at moms, dads, students and even kids.

We were all transformed into “consumerbots” — people living and working to buy bigger and more expensive things. Everything from computers to sports equipment suddenly became more specialized, and more expensive. The Great Race was on, and we all wanted to be “winners” and not the “losers” that I mentioned above. Everything became specialized, everything became commoditized; everything suddenly had a price, and every expenditure had to have a “Return on Investment.”

This highly competitive consumerist culture extended to everything from healthcare to education. The HMO Act passed under Nixon was a milestone in that it changed current laws to allow health insurers to make a profit. The once mundane banking industry was de-regulated to the point where banks now had marketing departments and product portfolios that they were selling to well-researched and well-defined market segments. And a university was no longer seen as a way to prepare young people to contribute to society, but rather as a way for individuals to invest in their own personal future net worth.

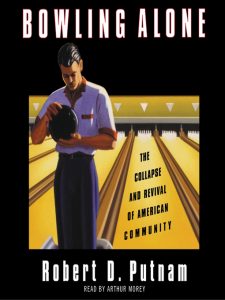

“Bowling Alone”

Robert Putnam wrote a seminal piece of work called Bowling Alone, which “shows how we have become increasingly disconnected from family, friends, neighbors, and our democratic structures”. His research started with an historical observation:

When Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States in the 1830s, it was the Americans’ propensity for civic association that most impressed him as the key to their unprecedented ability to make democracy work. “Americans of all ages, all stations in life, and all types of disposition,” he observed, “are forever forming associations.”

America used to be a nation of joiners. When I was a kid in the 60’s, I belonged to the Boy Scouts, the YMCA, Indian Guides, 4H and other groups. My parents belonged to sports clubs, social clubs, bowling leagues, bridge clubs. In our suburban neighborhood we kids would organize massive games of touch football and kick-the-can, often ranging through the backyards and woods of our neighbors’ houses for miles around.

Americans don’t do those things anymore. The Boy Scouts have been in decline for over a decade, social clubs are passé, and kids don’t just play with neighbours, their “play dates” are scripted and pre-approved. In Bowling Alone, Putnam noted that since 1975,

we sign fewer petitions, belong to fewer organizations that meet, know our neighbors less, meet with friends less frequently, and even socialize with our families less often. We’re even bowling alone. More Americans are bowling than ever before, but they are not bowling in leagues. Putnam shows how changes in work, family structure, age, suburban life, television, computers, women’s roles and other factors have contributed to this decline.

I maintain that it is Neoliberalism that has caused this massive change in American life. We have become consumerbots all seeking to maximize our own individual wealth and status in society at the implicit if not explicit expense of our fellow citizens. We have been brainwashed into thinking that the pie is only so big, and we have to make sure we get our share.

I maintain that it is Neoliberalism that has caused this massive change in American life. We have become consumerbots all seeking to maximize our own individual wealth and status in society at the implicit if not explicit expense of our fellow citizens. We have been brainwashed into thinking that the pie is only so big, and we have to make sure we get our share.

As I mentioned above, we have been convinced that we are in competition with our neighbours, and so we are less inclined to socialize with them or do things with them simply because they are our neighbors. The idea of play dates and finding “the best pre-k school” has expanded throughout our entire lives. Associations and social activities must provide their own “ROI” in terms of networking or making the right connections, meeting the right people, and so on. If you are a programmer or a banker, you want to hang out with other programmers or bankers. It would never occur to you to socialize with your neighbors if they are plumbers and electricians. But it didn’t use to be like that. America used to be a true melting pot — not just demographically, but socially. Not just on the national level, but on the neighborhood level.

Gentrification, Suburbanization and Homogenization

Most people have an idea of gentrification, the process by which a neighborhood or a city, town or other area becomes homogenized along socio-economic strata. Gentrification has become an accepted fact, a seemingly inevitable phenomenon, but this does not have to be the case. Indeed, gentrification has led to the point where cities are no longer built for people to live in, but for the rich to park their money in. We see this already in cities like London, New York, San Francisco and other bastions of financial or technology-based neoliberalism.

Indeed, gentrification has led to the point where cities are no longer built for people to live in, but for the rich to park their money in.

The Result of Neoliberalism: Sociopathy and Violence

San Francisco provides a microcosm of neoliberal dystopia, with the gaping divide between “winners” and “losers” in full display under the California sun. Here we have a concentrated cadre of elite “tech workers” — highly paid denizens of Silicon Valley — living among a sea of displaced, homeless and indigent people.

San Francisco provides a microcosm of neoliberal dystopia, with the gaping divide between “winners” and “losers” in full display under the California sun. Here we have a concentrated cadre of elite “tech workers” — highly paid denizens of Silicon Valley — living among a sea of displaced, homeless and indigent people.

What’s worse, almost 1 in 10 San Francisco homes is vacant. The city has one of the highest home vacancy rates in the country. These 30,000+ empty houses mean that the city could house well over 80,000 more people than it currently does. More than enough to house the 7000 homeless people currently living on the street.

But no. That cold irony is not a bug, but a feature of the system that decrees that people must be separated into winners and losers, haves and have-nots. THIS is what neoliberalism brings us — in a city full of homeless people, thousands of homes stand vacant. In a land of plenty, people go hungry.

The result is that friction builds; the “losers” see the injustice of the system; they fight back. Just as the wealthy cannot empathize with the poor, so have the poor lost their own empathy towards the rich, and towards each other. Fights over scraps can be the most vicious fights of all.

The anger, outrage, lack of empathy, growing isolation and desperation lead to violence. But Neoliberalism has a solution for this, too.

You see, once people have been driven so much into despair; once there are no good jobs to be had, no opportunity for advancement, once they perceive no future for themselves, they can be easily manipulated.

Enter the Military. The great equalizer, the great “meritocratic” system that rewards you with free college, free medical care, job security and a great pension.

All you have to do is be willing to kill people — and to die yourself.

For more on this, please read my next installment:

Other parts in this series:

- This is Neoliberalism, Part I: The 10 Tenets of Neoliberalism

- This is Neoliberalism, Part III: How We Build Empire

- This is Neoliberalism, Part IV: The Military Industrial Complex and the Big Lie Exposed

- This is Neoliberalism, Part V: the false promise of “Choice”

EuroYankee is a dual citizen, US-EU. He travels around Europe, writing on politics, culture and such. He pays his US taxes so he gets to weigh in on what is happening in the States.

Pingback: My Homepage

Pingback: This is Neoliberalism, Part IV: The Military Industrial Complex and the Big Lie Exposed – The EuroYankee Blog

Pingback: This is Neoliberalism, Part V: the false promise of “Choice” – The EuroYankee Blog

Pingback: This is Neoliberalism, Part I: The 10 Tenets of Neoliberalism | The EuroYankee Blog

Pingback: This is Neoliberalism, Part III: How We Build Empire | The EuroYankee Blog